Is it Really “Clean and Green”?

Overview of Industry Initiatives and Natural Gas Use and Production Emissions

The natural gas industry is currently spending lots of money to promote natural gas as a “green” fuel. In Ohio, for example, a congressional representative and an industry group have recently been promoting natural gas as clean and green:

But is it clean and green? When you look at Greenhouse Gas (GHG) emissions, the short answer is “no”, natural gas is neither clean nor green. When it comes to mitigating climate change, the answer is more complicated. Natural gas will likely play an important, temporary role in solving our climate crisis. Let’s take a more in-depth look at what this means, specifically when it comes to the use of natural gas in power generation.

Natural gas became popular for power generation when it became painfully obvious that coal power generation had to go. In the United States one dirty fossil fuel, coal, is being replaced by a less-dirty fossil fuel, natural gas.

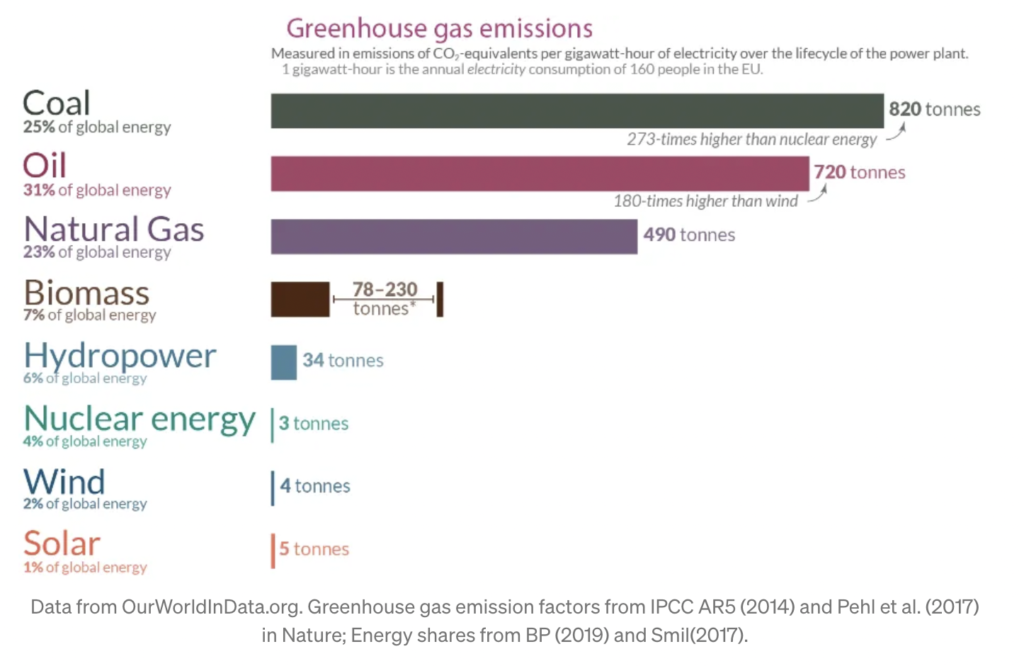

The good news is that this replacement resulted in lower overall carbon dioxide (CO₂) emissions, and part of the reason is that natural gas does have a lower rate of CO₂ generation than coal. However, CO₂ is only one of the family of Greenhouse Gases. The primary GHGs are CO₂, methane (CH₄), nitrous oxide (N₂O) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs). Here’s a comparison of total GHG emissions for various energy sources:

As you can see, natural gas is about 40% “cleaner” than coal, but this does not make it green or clean. The GHG emissions rate of natural gas is about 120 times higher than that of an objectively clean energy source like wind. And, one of the biggest issues with natural gas is that it is a significant source of methane.

The Methane Problem

Methane is emitted in natural gas production via leaks, tank venting and flaring (burning off excess gas). Methane is a powerful GHG: a single ton of methane in the atmosphere produces as much warming effect as 80 tons of CO₂ over a 20-year period.⁴

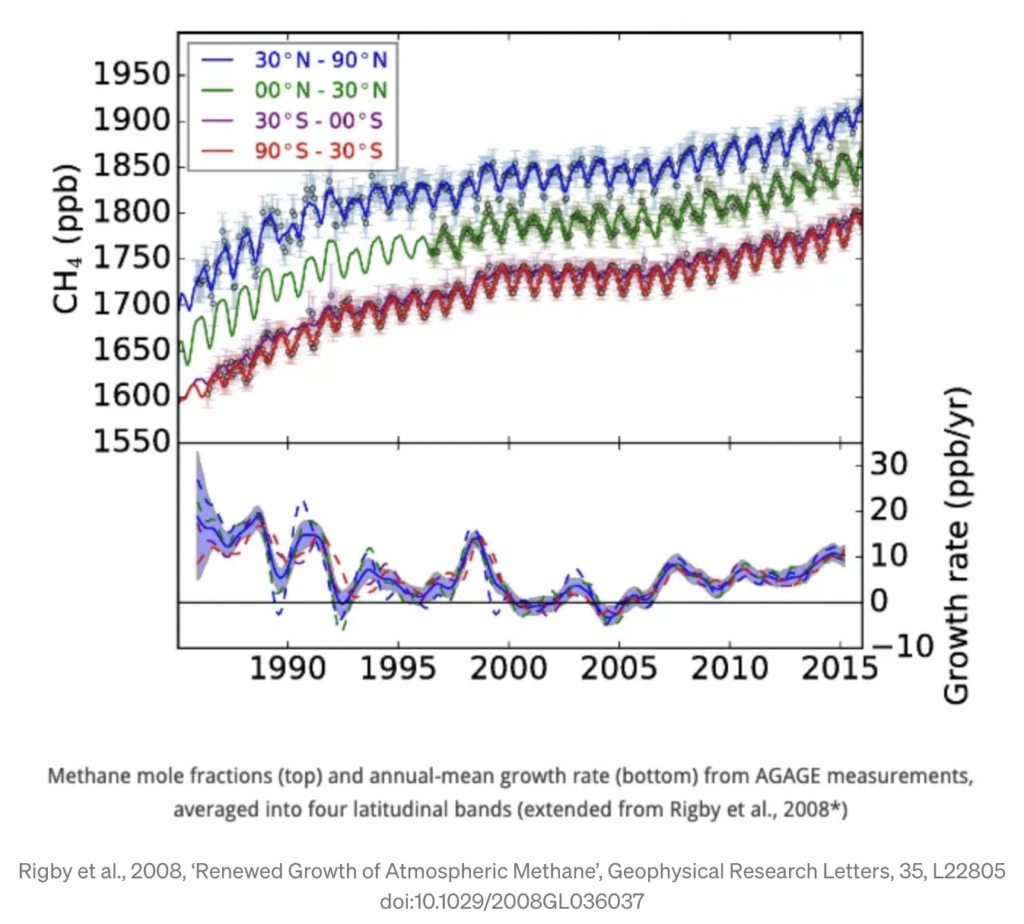

60% of the methane generated globally is from anthropogenic sources (people activities), and production of natural gas and other fossil fuels is a significant part of that. The concentration of methane in the atmosphere is getting worse.

The natural gas industry is generally in denial of this problem, but there are some encouraging trends with the larger fossil fuel producers. Chevron, for example, at its GBG field in the Permian Basin (west Texas and southwest Mexico) has made controls changes and other improvements to result in zero routine tank-venting emissions and no flaring.⁵ Furthermore, Chevron has committed to a 50% reduction in methane emissions by 2028 (compared to a 2016 baseline).⁶

The Future of Natural Gas

Natural gas is currently an important energy source. As the world transitions to renewable energy sources, natural gas can be viewed as a “bridge” fuel during a period of decreasing fossil fuel dependency. In some countries, stored natural gas in liquid form (LNG) is seen as a potential stored energy reserve for times when intermittent renewable sources are not available.

Let’s examine this “bridge” approach as proposed in the International Energy Agency’s (IEA) roadmap to net zero emissions (NZE) by 2050. It is not feasible to stop using natural gas in the near term. However, the roadmap projects natural gas-fueled generation (without carbon capture) rises in the short term, peaks by 2030 and is 90% lower by 2040.¹ Thus, natural gas can help bridge energy generation from where we are today to a climate friendly level of much lower GHG emissions, using different energy sources, in the future.

Natural gas could be of greater value and viable for the future if CO₂ emissions can be captured. This would be a vital step in making natural gas truly clean and green. There’s broad interest in doing this, and the U.S. Department of Energy (DOE) awarded grants in 2021 for a dozen projects to further develop the technology. You can read about the DOE program here.

The United States Congressional Research Service issued a report in 2021 on carbon capture and sequestration (CCS).² This in-depth report covers CCS and carbon capture, utilization and storage (CCUS). Utilization of CO₂ involves converting it into commercially viable products, such as

chemicals, plastics, fuels and concrete building materials.

Per the report, there’s much work to be done to achieve commercialization at scale:

- Current carbon capture costs are estimated at $43-$65 per ton CO₂ captured, though cost reductions of 50%-70% may be possible as the industry matures.³

- There are currently about a dozen U.S. facilities capturing and injecting CO₂ in chemical, hydrogen and fertilizer production, in natural gas processing, and in power generation.

- Costs have been, and remain, a key challenge to CCS development in the United States. (From Page 25 of the report.)

In a potential move to align with the IEA roadmap to net zero emissions, the natural gas industry has recently created a marketing entity, Natural Allies for a Clean Energy Future, to promote the idea that natural gas is “Accelerating America’s Transition to a Clean Energy Future.” One key aspect of this pitch is to utilize natural gas to provide power as a foundation for intermittent renewable sources, such as wind and solar.

Only July 6, 2022, the European Commission approved natural gas as a “green” source in the energy mix needed to enable Europe’s transition to a carbon-neutral future. This decision has been sharply criticized by environmentalists, but Europe is currently heavily dependent on natural gas, particularly with recent bans on Russian coal and the phase out of Russian oil.

Summary

Despite being cleaner than other fossil fuel sources, natural gas is not green and it is disingenuous to call it a clean energy source. It will, however, play a vital role on the path to net zero emissions as the world tackles climate change, with the IEA roadmap viewing it as a viable energy source in the next decade. If CCS and CCUS become economically viable, the use of natural gas either as a main source of energy or as support for intermittent renewable sources might continue well into the remainder of this century.

¹ Net Zero by 2050, A Roadmap for the Global Energy Sector, International Energy Agency, Page 117

² Carbon Capture and Sequestration (CCS) in the United States, Updated October 18, 2021 https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/R/R44902

³ Greg Kelsall, Carbon Capture Utilisation and Storage — Status, Barriers, and Potential, International Energy Agency(IEA), Clean Coal Centre, July 2020.

⁴ Standford Earth Matters Magazine, Methane and Climate Change https://earth.stanford.edu/news/methane-and-climate-change#gs.5gzn43

⁵ The Economist, “Cleaning up natural gas, Low-hanging fruit”, Technology Quarterly, June 25, 2022, Page 8

⁶ Chevron Corp. methane management https://www.chevron.com/sustainability/environment/lowering-carbon-intensity/methane-management